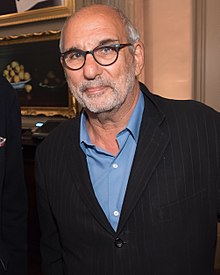

Alan Yentob

Alan Yentob CBE | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 March 1947 Stepney, London, England |

| Other names | Botney[1] |

| Education | King's Ely |

| Alma mater | University of Leeds |

| Occupation(s) | Television executive, broadcaster |

| Employer | BBC |

| Title | Controller of BBC2 (1987–1993) Controller of BBC1 (1993–1996) |

| Spouse | Philippa Walker |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Mother, Flora Esther Khazam. Father, Isaac Reuben Yentob.[2] |

Alan Yentob, CBE (born 11 March 1947) is a retired British television executive and presenter. He has held senior roles at the BBC including head of music and arts, controller of BBC1 and controller of BBC2. He stepped down as the BBC's creative director in December 2015,[3] and was chairman of the board of trustees of the charity Kids Company from 2003 until its collapse in 2015.

Early life

[edit]Alan Yentob was born into an Iraqi Jewish family in Stepney, London. Soon after he was born, his family moved to Manchester where his father was in business with his wife's family, the Khazams. One example of this collaboration were dealings in Haighton Holdings, published 1951, that shows involvement of his mother Flora, father Isaac and uncle Nadji Khazam.[4] Together they were involved in the UK with various other textile manufacturers plus wholesalers such as Spencer, Turner & Boldero and Jeremiah Rotherham & Co.[5][6] The families also had dealings in South Africa with their holding company Anglo-African Investments.[7] The public companies were eventually shed and a few consolidated into Dewhurst Dent, in which Alan Yentob still owns a 10% share.[8][9]

He grew up in Didsbury, a suburb of Manchester, and returned to London with his family when he was 12 to live in a flat on Park Lane.[10] He was a boarder at the independent school King's Ely in Cambridgeshire. He passed his A Levels and studied at the Sorbonne in Paris and spent a year at Grenoble University. He went on to study law at University of Leeds, where he got involved in student drama. He graduated with a lower second class degree (2:2) in 1968.[11]

Career

[edit]Yentob joined the BBC as a trainee in the BBC World Service in 1968 as its only non-Oxbridge graduate of that year. Nine months later he moved into TV to become an assistant director on arts programmes.[11]

In 1973, he became a producer and director, working on the high-profile documentary series Omnibus, for which, in 1975, he made a film called Cracked Actor about the musician David Bowie. In 1975, he helped initiate another BBC documentary series, Arena, of which he was to remain the editor until 1985. The series still returns for semi-regular editions as of 2014[update].

He left Arena to become the BBC's head of music and arts, a position he occupied until 1987, when he was promoted to controller of BBC2, one of the youngest channel controllers in the BBC's history. Under Yentob's five-year stewardship BBC2 was revitalised and he introduced many innovations in programming such as The Late Show, Have I Got News for You, Absolutely Fabulous and Wallace and Gromit's The Wrong Trousers.

In 1993 he was promoted to controller of BBC1, responsible for the output of the BBC's premier channel.[11] He remained in the post for three years until 1996, when he was promoted again to become BBC Television's overall director of programmes. This appointment was only a brief one, before a re-organisation of the BBC's executive committee led to the creation of a new post, filled by Yentob, of director of drama, entertainment and children's.[12] This placed Yentob in overall supervision of the BBC's output in these three genres across all media – radio, television and Internet. He occupied this post until June 2004, when new BBC director-general Mark Thompson re-organised the BBC's executive committee and promoted Yentob to the new post of BBC creative director, responsible for overseeing BBC creative output across television, radio and interactive services.

He also began to present BBC programmes. These included a series on the life of Leonardo da Vinci and, from 2003, a new regular arts series, Imagine. One episode of Imagine had Yentob explore the World Wide Web, blogging, user-created content, and even the use of English Wikipedia, exploring people's motives and satisfaction that can be had from sharing information on such a large scale. His own blog, created during the making of the episode, was subsequently deleted and purged.[why?] In 2007, Yentob appeared as the 'host' of the satirical Imagine a Mildly Amusing Panel Show, a spoof Imagine... episode focused on the comedy panel game Never Mind the Buzzcocks.[citation needed]

According to The Times, Yentob's reputation was affected when it was revealed that his participation in some of the interviews for Imagine had been faked. Yentob was warned not to do this again, but otherwise not disciplined, much to the disgruntlement of some who had seen more junior staff lose their jobs for lesser misdemeanours.[13]

In 2005, Yentob was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Letters from De Montfort University, Leicester.[citation needed]

On 17 March 2010, Yentob and Nigella Lawson opened the Jewish Museum London in Camden Town.[14][15]

In July 2009 he was revealed to have accumulated a pension worth £6.3m, giving an annual retirement income of £216,667 for the rest of his life. This is one of the biggest pensions in the public sector.[16] He earned £200,000 – £249,999 as a BBC contributor and presenter.[17] He was paid a declared salary of £183,000 by the BBC, but additional income from the BBC for presenting and other roles was reputed to earn him an extra £150,000, bringing his BBC income to an estimated £330,000.[18]

He has been on the board of trustees of the Architecture Foundation. He has been involved with several charities, including the posts of chairman and trustee of Kids Company.[19]

Yentob resigned as the BBC's creative director on 3 December 2015 in the wake of allegations that he had sought to influence the BBC's coverage of the Kids Company scandal.[20]

Kids Company

[edit]Yentob's role as chairman of the board of trustees for Kids Company, as well as the founder Camila Batmanghelidjh, came under close scrutiny following the collapse of the charity in early August 2015. He was accused of multiple shortcomings in oversight and financial management, and of failing to ensure that he avoided a conflict of interest with his position at the BBC. It was alleged that he intervened there in an attempt to deflect criticism of Kids Company and its founder Batmanghelidjh. Yentob vigorously defended his actions and stated in August 2015 that he was "not remotely considering" resigning over his behaviour.[21] However, he resigned on 3 December 2015.[20]

Interventions at the BBC

[edit]Yentob has acknowledged that he stood in the studio of the Today programme while Batmanghelidjih was being interviewed in July, later saying that he wished to hear what she had to say and was not attempting to intimidate staff. He also telephoned a senior member of staff at Newsnight, asking the programme to "delay a report critical of financial management at Kids Company", and telephoned the Radio 4 presenter Edward Stourton before a report in The World at One. The BBC Trust, under chairwoman Rona Fairhead, investigated these interventions, although senior BBC management were reported to have reassured the Trust that they did not compromise editorial independence at the BBC.[22]

"Descent into savagery"

[edit]Yentob has acknowledged signing an email from Kids Company to the government which sought millions in further funding by suggesting certain communities in London might "descend into savagery"[23] if Kids Company ceased its operations. The email, which was subsequently leaked to BuzzFeed News and the BBC's Newsnight programme,[24] spoke of "looting, rioting and arson attacks on government buildings" and warned of possible sharp spikes in "starvation and modern-day slavery".[23] It said that these concerns were "not hypothetical, but based on a deep understanding of the socio-psychological background that these children operate within".[23] Yentob said this email "was not intended in any way as a threat."[25]

Appearance before Select Committee

[edit]On 15 October 2015 Yentob and Batmanghelidjh made a joint appearance before a parliamentary Select Committee investigating the charity's collapse. Their performance was widely described as disastrous. In the New Statesman, the political commentator Anoosh Chakelian said they were a "duo of epically proportioned egos" who made "as little sense – and as many accusations – as possible"[26] before the panel of MPs. In The Daily Telegraph, the parliamentary sketch writer Michael Deacon called their appearance the "single weirdest event in recent parliamentary history"[27] and wrote of "three solid hours of bewildering excuses, recriminations and non-sequiturs".

Criticism from PACAC

[edit]The Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee report heavily criticised Yentob. He was described as someone who condoned excessive spending and lacked proper attention to his duties. The BBC is also accused of poor leadership for failing to take action against him when he tried to make suggestions about the BBC's reporting of Kids Company.[28]

Personal life

[edit]Yentob is married to Philippa Walker, a television producer.[29] He has two children.[30]

He was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2024 Birthday Honours for services to the arts and media.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ The Independent Independent:The Alan Yentob Experience

- ^ Yentob, Alan. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U41305.

- ^ "Alan Yentob steps down as BBC creative director". BBC News. 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Haighton Holdings". The Guardian. 15 November 1951. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Shares in Anglo-African Finance and Dewhurst-Dent". The Guardian. 28 June 1983. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Spencer Turner & Boldero and Jeremiah Rotherham". The Guardian. 24 January 1967. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Don Wilkinson Local takeover of Khazam Yentob group rumoured The Citizen, Johannesburg, DTIC ADA346221: Sub-Saharan Africa Report, No. 2830, P.111' 28 June 1983

- ^ "Maverick Child of Auntie". The Observer. 28 April 1985. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ BBC Declaration of personal interests (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2012, retrieved 22 December 2011

- ^ Lister, David (29 May 1999). "Profile: Alan Yentob: The insider's extrovert". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Davies, Hunter (9 March 1993). "He's in control: Alan Yentob decides what you will see on both BBC channels. He is far from a Corporation man, but then he's only been there for 26 years". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Alan Yentob, Creative Director Archived 12 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine", BBC. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ Hamilton, Fiona; Coates, Sam; Savage, Michael. "BBC row as Alan Yentob is let off for fakery – Times Online". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ^ Evans, Kathryn (16 March 2010). "Nigella Lawson and Alan Yentob open transformed Jewish Museum in London". Culture24. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Lawless, Jill (17 March 2010). "London's Jewish Museum reopens after major facelift". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 December 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, Fiona; Coates, Sam; Savage, Michael (5 July 2009). "Licence payers fund BBC chief's £8m pension". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew; Obordo, Rachel (19 July 2017). "BBC accused of discrimination as salaries reveal gender pay gap – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ James Legge (6 June 2013). "Alan Yentob paid two salaries by the BBC". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Kids Company | Annual Report and Accounts Year Ending 331 Dec 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ a b "BBC's Alan Yentob resigns". BBC News. 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "BBC's Alan Yentob 'not considering' resigning over Kids Company claims". The Guardian. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Plunkett, John (19 October 2015). "BBC Trust quizzes Tony Hall over Yentob's Kids Company activities". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Kids Company Chair Signed Email Warning Of 'Arson Attacks On Government Buildings' And "Savagery" If Charity Closed". Buzzfeed. August 2015. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Wright, Oliver (25 August 2015). "Kids Company: Leaked email warns of 'arson attacks on government buildings' if charity were to close". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Burrell, Ian (12 October 2015). "Kids Company Alan Yentob confident backers of collapsed charity can continue to support children". The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Chakelian, Anoosh (15 October 2015). "'Verbal ectoplasm': what happened at Camila Batmanghelidjh and Alan Yentob's Kids Company hearing?". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Deacon, Michael (15 October 2015). "Alan Yentob's day of embarrassment over Kids Company... from £150 shoes to abusive limericks". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "'Catalogue of failures' hit Kids Company". BBC News. 1 February 2016. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Hamilton, Fiona; Coates, Sam; Savage, Michael (13 September 2006). "BBC chief's son is stabbed by robber at family home – Times Online". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ 15 November 2004 The Alan Yentob Experience, Media, News, The Independent

- ^ "Birthday honours: Mark Cavendish, Strictly's Amy Dowden and Alan Bates recognised". BBC News. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1947 births

- Living people

- Alumni of the University of Leeds

- BBC executives

- BBC One controllers

- BBC television presenters

- BBC television producers

- BBC Two controllers

- British Jews

- British people of Iraqi-Jewish descent

- Businesspeople from the London Borough of Tower Hamlets

- Grenoble Alpes University alumni

- People educated at King's Ely

- People from Stepney

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire